| | Poverty of the Heart | | Speaking at the UN Ingrid Stellmacher explores 'Poverty of the Heart' and launches the Dignity Diaries, as a tool to discover what dignity in toay's world really means.

More ...

|

| | World Heart Day | | On World Heart Day Ingrid writes about the other heart that's just as important for our survival and the need to recognise it.

More ...

|

| | |

|

Ingrid's Insights

When The price we pay for Dignity and honour is poverty of the heart

Ingrid Stellmacher speaking at the United Nations in New York in 2014 to 400 NGO's during the launch of The Dignity Diaries.

The below includes extracts from her speech 'Poverty of the Heart'

Excessively patriarchal societies breed a harsh form of poverty. Polarising power, division, exclusion and discrimination. All of which contribute to escalating levels of violence, that all too easily become the norm.

We see it happening all over the world - all of us in this room, in the work we do, in some of the political institutions with which we engage, and for some of us - even in our own homes. Poverty has many faces, many causes, with some effects hiding in plain sight. It cripples humanity from the inside out and when it does, it creates another form of poverty 'Poverty of the heart'.

Research shows that the lack of development to connections in areas of the brain, through continual destructive and violent behaviour, limits the ability to exercise compassion and recognise emotional responses in others. It slows the ability to communicate effectively, emotionally, and the most basic requirement of all, for humanity, limits the connections in areas of the brain that enables empathy.

The way we treat one another, speak to one another, look at one another, or exclude one another, affects our own mental and emotional development, shaping who we are and the way we live. It is a vicious cycle of destruction for everyone involved. Forever treating a single group or person badly, literally leaves those neural pathways to possibilities and capabilities so neglected, that the conversation between our head and our heart becomes the ‘road less travelled’.

I am not speaking of the victims of violence and discrimination here, but more of the effect that the act of repeated violence and exclusion, carried out against an individual or group, has on the person doing it - the perpetrator. What it does to them on the inside, especially in the way their brian develops as they become wired for violence.

Sanctioned by the culture you live in and woven into values backed up by laws to contain you, there is little chance of escape. So what can we do to stop the violence inside and out? In trying to grapple with any behaviour change we need to understand what has shaped it and what lies beneath, to create different approaches because your values shape the way you see the world. And if you live in a world without compassion, how will you know what it looks like? What it feels like? How will you change it and why would you change it? What would be in it for you?

Dignity Diaries

In looking at poverty of the heart, I have been working with the role that dignity plays in our lives. Some tell me it is an old-fashioned word, an out-dated concept, no longer relevant for today. But it is relevant, for human dignity is the defining pillar upon which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights itself rests. Arguably the most important post World War II document created. If dignity is weakened the world is weakened. In my work, I have found dignity to be like peace and like love - you can’t touch it, you can’t buy it and you can’t hold it in your hand - but you know when you don’t have it.

Like peace and like love, dignity is best known by its absence. Its forced absence all too often used as a tool of war – to humiliate. And humiliation is contagious. So, do I belive dignity is still relevant in today’s world? My work shows that it is and without it we lose a glbally agreed benchmark of behaviour.

But dignity is a complex concept, closely entwined with identity, with honour, with shame, with guilt, and humiliation because human beings are complex. And because I work with human beings and their complexities, the often, fragile concept of dignity is the focus of a programme I am launching today called the Dignity Diaries. Interviews providing insights and learning on the impact of dignity lost, or dignity reclaimed, in the lives of those at the heart of events from all over the world, reminding us of our value and that humanity still have much to learn about itself and our attitude to the planet.

Dignity Diaries

In one Diary, Ziauddin Yousafzsi, who you may know better as the father of Malala, the Pakistani schoolgirl short by the Taliban 2-years-ago, for daring to go to school, Ziauddin, now UN Special Advisor for Global Education, vividly describes how 'he did not clip the wings of his daughter in the name of, false dignity and false honour'.

'Freedom is her right' he declares, his own bravery revealed. But it was not until speaking about the role that dignity and honour plays in his culture, exploring it in conversation - that he understood how it much contributed to the shooting of his daughter in trying to keep their lives small. Cultural norms have a habit of hiding in plain sight.

There is a moment in his Diary when his voice drops and he quietly shares how 'He feels ashamed to be a man sometimes', when he thinks about ‘how badly and unfairly men have treated women in his culture’. It is a moment of humility against the background of a brutal reality, that many men face around the world, and we need to find a way to engage with them and support them - as much as we need them to engage with us.

'Most forms of poverty we are familiar with but poverty of the heart is the road less travelled’

We are all familiar with the economic poverty of women excluded from contributing fully to life; keeping their world small. We all know that limiting the contribution of women, limits prosperity for families, communities, and economic growth. We know when women lose, we all lose.

Everyone in this room knows the impact of poverty of choice. When women are excluded the right to determine who has power over their own body; their own minds, and their own lives. When girls as young as eight years of-age, many already maimed by FGM, are sold to pay off debts, without choice or power, to voice their own opposition, being married off to ancient men to have children with, when still only children themselves.

And everyone in this room knows that excessive patriarchy breeds poverty of education, access, and opportunity, including basic health education for their children. When babies and infants are dying of malnutrition in Afghanistan not just through lack of food, but through lack of the basic education allowed to young mothers on baseline nutrition and what babies need to be healthy. Not because that information isn't out there but because women themselves are not allowed ‘out there’. Out of their homes to access the education for themselves and their children, by their husbands, their brothers, their uncles, cousins, until they want to, all in the name of dignity and honour. Arriving at clinics sometimes so late in their child's illness that when they do get ‘out there’, their babies are too sick to save.

Dying of starvation is tragedy enough. Dying of deliberately created ignorance and prevention of access to the right to health, is a crime - because these deaths are Avoidable. What gives them the right to choose a child will live or die? Not their mothers and certainly not their faith.

----------

Research shows that different values activate different thought structures within the brain and even show that different areas in the visual cortex, the area which processes what we see, is activated in different ways, according to different cultural values and beliefs. Creating a fundamental difference in the way we see the world and act towards others. It is a difference we have to recognise the importance of - not just in our work - but in our world in general. Because our values, act as an anchor of certainty in an ever increasing uncertain and unstable world – we need them. We hold on to them at any cost. They create a framework by which we live, however harsh. We fight for our values, go to war to defend them, commit unspeakable acts in their name - but there are no winners in war – everyone loses in one way or another and that all important framework of values, in the end is all too often left in tatters because of the lines we cross to protect them.

'Every daughter is like Malala in wanting an education', Ziauddin explains, and while I’m sure that desire is true, sadly every father, however, is not like him. We need to work together with men across civil society and politics to help one another.

Dignity Diaries

In his Dignity Diary, Andre Mostert a lecturer from South Africa, talks movingly about ‘white guilt’ how it affected him growing up under Apartheid, and how 30 years later - it affects him still. What touched me most is when he recalls the moment black South Africans finally got the vote and the lines of people waiting were so long, that he and his school friends decide not to queue…..

"The world had moved on right, but for us spoilt white boys, it was just voting yeah. So, we go into a pub and watch it on TV. And I'll never forget, we were sitting there watching journalists talking to people, standing in those lines for hours, that went on forever, and this one journalist goes up to an old black woman waiting patiently in line and says to her:

'How long have you been waiting in this queue? She turns to him and declares:

'My whole life."

Says Andre “I get goose bumps even now just thinking about it. Because it was the moment I realised this isn’t just about them – or one side against another – it’s about us! It was about us getting our dignity back, because we gave them their dignity back, simply on-the-basis of being human.”

--------------

When I showed Andre’s Dignity Diary to young women at a workshop in Rajasthan, India, for the Guild of Service. I asked Merra Khan, the Guild’s deputy, how long she had been waiting in the queue to make a difference to the lives of widows in India she had dedicated her life to - the answer she gave: ‘2000 years.’

-----------------

The good news is that narrowed network of neural development, can be changed, it can be expanded. The world can grow bigger and more beautiful. Unexplored emotional areas of the brain can be activated due to its plasticity and new pathways in the language of empathy and compassion forged. We can break out of that cycle of fear and negative behaviour - we can become whole again.

------------

Most of us in this room today, have been working our whole lives to get to the front of our own queue – like Merra and like the lady in South Africa. We work to change things in ways that we can, to make a difference, to make something of meaning, to leave a legacy.

The Dignity Diaries is my way – I know you have yours, that’s why you’re here today, in the Dag Auditorium at the United Nations, as we take heart from each other and share what we’ve learned. I hope you will join me in exploring how we can implement the Dignity Diaries in our own areas of work.

Please, sign up - and maybe someday soon we’ll meet up at the front of the queue or better still, there won’t be one anymore. ….

Thank you.

Interviews with Ziauddin Yousafzsi and Andre Mostert can be found by clicking on the link 'New Global Conversation' Dignity and Honour Campaign on our home page. www.lemenachfd.org

|

0 Comments

|

Permalink

|

Looking for Elsie

Ingrid Stellmacher leaving Carteret Harbour

In the early hours of 11th August 1948, two lovers stole a 12-foot dinghy from Carteret harbour in northern France and rowed

14 miles through rough seas to Jersey. The wooden boat bore the name ‘The Elsie’ and the name of her builders who were English:

J Husk Jnr of Wivenhoe.

Eight years later those lovers would become my parents and the story of my father’s promise to come back for my mother when the war

ended, and his 14-hour battle with that stretch of water’s unpredictability, one of the most dangerous tides in the world, became

part of our history and their strenght our legacy.

Sixty-eight years later, I made that same journey my parents did. What took my father 14 hours though to row, took us barely 2 hours in a Rib,

and Jersey’s Rowing Club’s competitors, just over 3 hours with a 3 man crew in their races across the same waters. My father’s battle to navigate

Jersey’s treacherous rocks and unforgiving tides that night, to stop the boat from being pushed further off course and out into open sea, was

one my mother was convinced they wouldn’t win at times.

“I saw blood trickling from the corner of his mouth” She recounted. “He so was tired, the tide was so strong, the waves so high, and I thought

that’s it! After everything we’ve been through we're going to die here!"

But my father's metal battle with the tides and his own exhustion won through and I have often thought about 'The Elsie’s' part in that journey. How she came to be there that night and who the woman the boat was named after was. For while Elsie appeared at the right time on the righ night for my parents to make their escape it was also Elsie’s presence that betrayed them, alerting harbour authorities of her secret arrival on the island. Having made it to the last piece of land possible before overshooting Jersey altogether, my parents came ashore on a small rocky inlet at Vicard Point near Bouley Bay. From there the only way out is up. Forced to abandon Elise in full view, they scaled the Point’s dangerously steep cliffs and made the 5 kilometres into St Helier. From the moment they left Elsie the authorities began to search for spies arriving illegally on the island rather than lovers looking for sanctuary, to marry and start a new life. A life that would eventually lead they hoped

to England and settle amongst the British for whom my father had spied for during the war.

Trapped on the rocks where my parents abandoned her, Elise, pounded by the waves, broke up, and all that remained intact when she was salvaged were her ores and pieces of her that revealed her name and builder - not a French boatbuilder as expected along with the name Elsie, decorated with a blue star either side. An afterthought added later perhaps?

John Collins, a key member of Wivenhoe’s History Group in Essex and authority on maritime history, tried tracing a boat named Elsie built

by J Husk & Sons but drew a blank.

‘It’s possible she had been built by Husk’s but not the yacht itself.’’ Explained John.

“Husks only built boats and dinghies for vessels that they hadn’t built themselves, often as replacements, and mostly for yachts and

fishing vessels.”

He did find one boat named Elsie though, last registered to a Mr Albert Glandas, fils, in Havre. Could this be Havre-de-Pas in Jersey?

The Elsie registered to Glandas was built in 1875 but John couldn’t trace her beyond 1899. That she would have survived the war years

and ended up in Carteret 51 years later is unlikely.

Peter Hall, Chairman of the Wivenhoe History Group, revealed that a fishing smack by the name of Elise was well known in Wivenhoe,

owned and raced by Friday Green, who won the America’s Cap and already detailed on Wivenhoe’s History website.

https://www.wivenhoehistory.org.uk/content/topics/maritime/mike-boats/friday-green-and-elise-ck299

Could it be the name Elsie was recorded incorrectly by the authorities when wrting up the report and was really a second generation Elise from Wivenhoe? The builder after all is recorded as J Husk Jnr, not J Husk & Sons?

Is there someone out there with clues about the boat, or the name of the lady she was named after?

And my parents? They were spotted at sea heading towards Vicard Point the same afternoon they beached Elsie. Quickly found, the boat made headline news

in Jersey’s Evening Post, prompting extra police activity on the island which unlike mainland Britain, had been occupied by the Germans during the second World War.

Three days later, anxious that they would ultimately be identified and arrested anyway, my parents, exhustated after their incredibly journey, having stolen a boat, entered the island illegally and made false declarations when registering at a bed and breakfast, gave themselves up. They were arrested, held in custody, and 4 days later after a court hearing, deported to a jail in France having been banned from going back to Jersey for five years.

The mystery of Elsie remains unsloved but my parents fight for how and where to be together was solved. They made it to England where they married later that year, in the beautiful county of Kent, after 43 love letters, 1 promise and 9 years in between. They were together 59 years.

They never returned to Jersey.

|

0 Comments

|

Permalink

|

In our right minds?

57th Commission on The Status of Women

'In our right minds', was the perfect title for a session at this year’s United Nations Commission on the Status of Women in New York. Not because it’s the name of Dale Allen’s one woman show, the main speaker at our event, but because who in their right minds, of all the delegates, NGO’s and agencies attending one of the largest international forums in the world, could possibly think that we can actually ‘prevent’, never mind ‘eliminate, violence against women and girls in our lifetime? The title theme of this year’s 57th meeting of the Commission?

I had the privilege of being the opening speaker at the session, sponsored by Montage Initiative; a US based organisation working to create sustainable livelihoods for women in India. The participants purposefully reflected not only a range of expertise and experience but also the rarity of wisdom and youth as well as generation and gender; constituencies that must work together to help counter violence against women and girls.

|

Dr Mohini Giri - Head of Guild for Service, India. Photo by 'ar'

|

The wisdom manifested itself in the form of 78 year-old veteran activist and scholar, Dr Mohini Giri, former daughter-in-law of President V Giri of India, and Head of India’s Guild for Service. Dr Giri, who saw first hand the affects of widowhood in India when her own father died, and who was later herself widowed, helped found the Guild in 1972 and works tirelessly to improve the lives of widows in her country. Numbering a staggering 42 million, many of them barely surviving and living on the streets, widows find themselves betrayed by a culture commonly lacking in compassion for its women, in a country beset by corruption that is flagrantly active at all levels of society and governance.

Dr Giri’s tiny bespectacled frame belies her huge passion and commitment, undiminished with age, that bubbles just beneath the surface. Her opening words, that ‘patriarchy breeds poverty’, were received with nods of agreement from an equally distinguished audience and her sense of urgency for action only increased with the announcement that she had just delivered a declaration to the UN, requesting the rights of widows be formally recognised as a United Nations Mandate.

Violence against women and girls has for so long been firmly framed as a ‘woman’s issue’; a messy subject like menstruation; a taboo that no one wants to talk about, with some cultures in silent collusion more than others. But the thing about women’s issues is that they are for the most part, more about men than they are about women. Particularly in cultures where men have absolute power over women and corrupted that partnership absolutely in many cases, disastrously holding those cultures back socially, emotionally and economically. Even in the case of FGM, where it is mostly women themselves perpetrating and perpetuating the practice, it is with men in mind, marriage, and the need to be identifiable as a virgin, that young girls continue to be subjected to this ritual. Who will want them otherwise?

|

UN Per Carlos Garcia-Gonzales, El Savlador. Photo by 'ar'

|

Which is why it was essential to have a male voice on our panel to provide that additional perspective to the discussion. That voice was the UN permanent representative to El Salvador, Ambassador Carlos Enrique Gonzales-Garcia, and this year’s Vice President of the Commission. For how can we talk seriously about ‘women’s issues’ without including men?

The lack of men on other panels in some of the sessions I personally attended was disappointing. In an early one on eliminating violence, where increasing political accountability and addressing structural violence was high on the agenda, not a single man was on the panel comprising senior UN agency heads and government ministers from around the world. As heartening as it is to see women heading these organisations and holding ministerial posts, when the obvious absence of men on the panel was raised during question time by a young man working for the UN himself, the response from the chair was decidedly brief and vague, as if wrong-footed by a question that was totally unexpected.

Self deprecating and with equal amounts of humility and humour, Ambassador Garcia animatedly spoke about the need for accountability, calling for an end to impunity in cases of violence against women and the need to work together. Not just top down, through political policy, or bottom up through social movements but sideways as well. Integrating and collaborating with one another, with organisations dovetailing to create a whole approach to issues as never before. Not just soft power in action but the judicious use of smart power in pulling it all together.

Garcia is a huge advocate of El Salvador’s ‘City of Women’ Initiative - Cuidad Majure in Spanish, supported by the country’s first lady, Vanda Pignato, who is also the Secretary for Social Inclusion. It is more than the usual one-stop social shop for women providing refuge from violence, however. City of Women will provide childcare, police support, help and education on legal and civil rights, job training and a raft of other meaningful integrated services.

The plan is also to provide entrepreneurship opportunity as never before, creating confidence as well as competence. Crucial components for what could create a huge cultural shift regarding women if this initiative’s success equals its ambition. And with these centres set strategically around the country, connecting holistically with one another, not only will whole communities benefit from such collaboration, but the whole country as they form a new social, emotional and economic infrastructure driven by women. This is not just an initiative with guts but one with heart and a model to be applauded, adapted and adopted around the world.

|

Klevisa Kovaci & Sharon Pedrosa, Chair & Co

Founders, Student Advisory Board, Montage Initiative. Photo by 'ar'

|

And finally at the other end of the generation scale, the youth and enthusiasm on the panel came from the Co-Chair and founders of Montage Initiative’s Student Advisory Board, Klevisa Kovaci and Sharon Pedrosa. These young stars from Fairfield University are no longer leaders in the making for they have already demonstrated they are leaders and role models, working for the empowerment of young women not simply as a cause to champion but as a way to convert energy and ideas into action.

With polished professionalism Klevisa and Sharon spoke about creating a ripple affect of change through the board they had founded and model they created for youth empowerment. They outlined the need for other organisations to be more aware of how educational opportunities in Service Learning can reap real dividends for both parties if viewed as an investment and how they themselves had benefited from Montage’s student programme.

Given meaningful mentorship and responsibility, rather than filing and making tea, these young women had become not only mentors themselves to their peers but real decision makers in their own right. Along with several other Montage student colleagues, they had organised and co-ordinated most of the UN event themselves and even the camera crew filming the session were students from another university. Showing just what young men and women can do given the opportunity to collaborate and shine.

As Sharon put it, “Only a year ago we visited the UN during the Commission on the Status of Women for the first time with Montage and now look at us; we’re actually speaking here! And if we can do it, anyone can do it”.

|

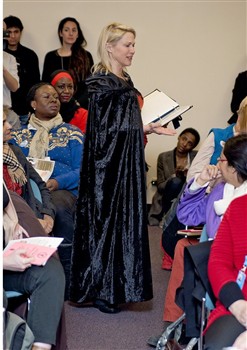

Dale Allen - Photo by 'ar'

|

Last in the line up came Dale Allen. Reading with authority as she stepped slowly through the room, her entry was theatrical. Wearing a full-length black cape she read from a large book, quote after quote, of different religious text from around the world that collectively demonised and denigrated women throughout history. The largely unsuspecting audience were spellbound by her delivery as much as stunned to hear women officially declared not only worthless but also evil across the continents, through the ages and in every holy book.

Travelling quickly but seamlessly through time, Dale recounted how women of early cultures were honoured as goddesses, protectors and co-creators. How their fall from grace began slowly with the advent of the alphabet, writing and reading. The different way in which the brain needed to process this new form of information was also the beginning of its rewiring and the great switch over; like going from analogue to digital. From previously, image orientated right brain soft skills of creativity, empathy and intuition associated with feminine qualities, to left brain, hard analytical skills of logic, reasoning and linear thinking; traditionally attributed to male ways of seeing and being in the world.

Leonard Shlain, put forward the hypothesis of the alphabet as the ancient female nemesis, in his book the ‘Alphabet versus the Goddess’ published in 2004, in what he describes as the 'conflict of word over image'. As a consequence the written word became the God of all things; over symbols, sex and of course women. Dominating a world where feminine attributes had previously held the greater currency.

But technology and the keyboard is our saviour apparently and its widespread use in our offices, our homes and on the move, by both sexes, is activating left and right brain connectivity in a new simultaneous conversation as never before. Rewiring new areas of our brain and encouraging not only new pathways of connectivity but greater access to creativity and enabling men in particular, to see the world through new eyes. If the left brain/right brain theory holds validity then announcements from the scientific community last year that the human race had reached its evolutionary limit, as there is no space left inside our skulls for our brain to grow larger, then perhaps our brain rewiring itself is where the real action and evolution is; the sum being greater than its parts.

'The human race has reached its evolutionary limit'

The human race is now exposed to more information in a single day than our 15th century ancestors were exposed to in an entire year. But while the proliferation of ‘experts’ online makes more information available to the masses it does not necessarily make us wiser as a result. Information is simply knowledge. The wisdom lies in how you apply it. If Shlain’s theory is to be believed, not only is the use of our keyboards helping to balance out our brain but being bombarded by images through our TV’s, PC’s and hand held devices 24 hours a day maybe another contributing factor. Images being processed in the right, more ‘feminine’ part of our brain.

Dale ended her contribution with a heartfelt song about the long and lonely wait for the return of the soul; the archetype that is woman and the feminine, to an eruption of emotion and applause. Joanne Watkins, my close friend, colleague and CEO of Montage Initiative, had achieved what she set out to do; deliver a session on empowering women using different ways of engaging; through words, images and theatre and one that will be remembered for the unique why in which stories were told and issues were touched.

Memorable as it is however, in the time it has taken you to read this, somewhere in the world a woman has been raped, a child abused, and a life will have been broken forever. Against the backdrop of the cavernous collective wound of daily violence against women, that mankind continues to inflict on itself, what difference do all the statements, sharing and networking at a meeting of this magnitude make?

What can we take away from our own session and this year's Commission as a whole? What was clear, is that language and meaning is a key factor in both the sharing of best practice and its delivery. The shameful failure to agree acceptable conclusions at the end of last year's Commission was due to differences of language and terminology in the final draft document, which contained so many strike throughs and deletions it was rendered virtually incomprehensible. A repeat of a similar roadblock has thankfully been avoided this year.

'We want more mentors and less monsters'

Now more than ever we need smart, collaborative, strategic thinking and action if we are to succeed and making use of technology and big data in creative ways. Both as organisations, and in the use of our tools, approaches and resources from every possible avenue. Conventional and crazy; top down, bottom up and sideways. From left of field and right to the heart; from social media to individual effort leading to widespread co-operation at scale. Culture change comes through a number of different influences; including education, communication and imagination. Their effects converging in the mother of all tipping points when the 'hundredth monkey has joined the 99' and the timing is ripe for change. Most of all change comes when people have had enough. It is crucial for men to be involved in the culturally sensitive conversations needed at every level along with the concrete commitment at the top that is sadly lacking right now. We need more men to stand up and stand by us, as role models as well as change agents. We want more mentors and less monsters.

While introducing an additional perspective of difference between the sexes that could supposedly change mankind for the better if united, does pose an interesting hypothesis, the real meaning behind Dale's story is to help women understand and maybe even remember, that once upon a time it was different and that they must hold on to the hope that one day it will be again. This is what keeps us striving towards our common goals on the long road towards fighting violence against women and girls. We know that culture change is a long and complex process and that working together we can make a difference. The belief in that is part of why we have come. Not to just to share and learn together but to renew our hope together. For without that, our task surely feels insurmountable and we will have lost everything.

Poetically, ho pe comes in many forms. The ancient Greeks had a Goddess of Hope named Elpis, who alone stayed on earth to comfort mankind after all other spirits had fled. That the ancient Greeks made the quality of hope itself feminine is perhaps even more relevant in the present. pe comes in many forms. The ancient Greeks had a Goddess of Hope named Elpis, who alone stayed on earth to comfort mankind after all other spirits had fled. That the ancient Greeks made the quality of hope itself feminine is perhaps even more relevant in the present.

The Greeks had another Goddess named Nemesis. She is the Goddess of Retribution whose job it was to restore balance to the world. In order to do so, however, she had first to destroy it to pave the way for its rebirth. If we can't stop the worldwide epidemic of violence against women and girls soon, the perpetrators might beat Nemesis to it.

Elpis - Greek Goddess of Hope

|

Ingrid Stellmacher, 08/03/2013

|

0 Comments

|

Permalink

|

World heart Day

As today is World Heart Day I want to talk about the heart. But not the one promoted globally by the World Health Organisation and the United Nations, to raise awareness of how not looking after it has become the No 1 killer in the West. Or the one that without proper nutrition in children, inhibits its ability to develop and function effectively against infection or disease, like Malaria or malnutrition; the No 1 child killer’s outside the West.

I want to talk about the other one: the heart that has no physical location. That unlike its counterpart embedded in our chest and without which life cannot go on, is without fixed location, and without which, feels life is not worth going on. So I will speak from my own heart. My compass for over 50 years so often ill read by me, much less listened to at times, but which I believe the care and wellbeing of in us all, to be of equal importance and more than worthy of a global day of recognition.

For so long designated as a place of weakness rather than strength, dictated by emotion rather than logic so considered less reliable. The existence of this ‘other’ heart, which cannot be touched or quantified is marginalised in government while idealised in story, poetry and song. And because the language of the heart speaks in actions not words, is harder to hear, get quotes on, and underestimated in business, politics and the exercise of power. Most of all I suspect it is because the most powerful, uncontrollable and unquantifiable commodity of all is said to reside there, and of course the most complicated and desired. Love.

That word ‘heart’, in this other context, like the words ‘peace’ and ‘love’ are what advertising agencies call ‘big’ words; meaning different things to different people and that’s the trouble. It’s difficult to define because to do so immediately confines its power and its meaning. The heart is full of feeling and emotion. Learning to understand our own, let alone anyone else’s, is a lifetime’s work. Learning to understanding the feelings of another culture may take longer still but making efforts to understand it is an absolute necessity. As Pakistan’s declared ‘Day of Love’ last week, in honour of the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) as a man of peace is testimony to just how complex the language of the heart truly is and how dangerous it can be when ignored.

Emotions matter. They are the new rulers of the 21st Century as uprising after uprising around the world has shown, creating a new emotional map and new vistas. Making history and culture compulsory, not only in international relational programmes but schools and colleges around the world, is imperative if we are to navigate this terrain with some success. When one extremist voice speaks to another, the hidden language behind what is said is equally important to hear as the voice in the middle that gets drowned out or caught in the crossfire.

And my own heart wondered what the Prophet Mohammed, (PBUH), would think of the death, destruction and division unleashed and acted out in his name. I wish I could sit with him and ask him. The same way I wonder what Jesus would make of the fights between Greek and Armenian clergy that break out with regularity at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Some years ago I was invited to do a conflict resolution workshop with a group from Pakistan. As I stood at the front of the room and the men only class sat waiting for me to start, an elderly gentleman rose to his feet. The harshness of his life etched so deeply on the contours of his face it resembled the surface of a well weathered tree trunk. Shouting at me and waving his arms he began blaming me for every misdeed done during the reighn of the British Empire and everything they might do in the future. No one intervened or asked him to sit down and I suspected they wanted to see what this lone British woman was made of.

He continued shouting in his broken English, made all the more incomprehensible by his lack of teeth. I shouldn’t be here! I am a woman! I am a mother! I should go home! He continued ranting for several minutes more before people fed up with the sound of his voice and realising I was showing no signs of weakness or going away, asked him to sit down – which he didn’t. So I took a breath, a step, and spoke from the heart, and asked him, “Has your anger hurt you enough?”

Silence settled on him and the class so quickly you could hear a pin drop. The energy in the room changed immediately. I looked him in the eyes and asked him again. “Has your anger hurt you enough?” In that moment if my heart had burst though my chest and fallen to the floor I would not have been in the least bit surprised it was beating so hard, and thankfully audible only to me. My gaze held his as it does when you really look at someone. When you really see them, and your eyes meet their's in that place where there’s nowhere to hide. We stayed there for what seemed an age but was only seconds as I took a step closer and asked him, quietly this time, “Has your anger hurt you enough?”

The silence grew louder. He didn’t cry and the tears that filled his eyes didn’t spill over or roll down his face. He held back with a dignity that everyone shared, and instead, slowly and silently, he simply sat down. I knew he had just made the longest journey of all. The one from his head to his heart and he had taken the whole class with him in a nano second.

It wasn’t me he was shouting at or me he was angry at. It was his situation. His ‘government’s inability to govern’ he later told me. The lack of equality, safety, healthcare, electricity, iniquities and history that made everyone in that room the walking wounded. He ranted at me because I was from the ‘West’. He ranted at me for all the times he wasn’t heard by the people he felt should have listened. He ranted at me because he was in pain, he ranted at me for everyone’s pain ignored. He ranted at me because I was there. He ranted at me because he could.

Turns out the old man who was only 49 years-old and had educated over 400 girls in Sindh and Balochistan. He was a one man NGO affiliated to the United Nations and dedicated his life to improving the lives of young women and girls. I knew the huge efforts and sacrifices he must have made to do this and I was humbled. He humbled me further at the end of the day, by making me a gift of a book he carried with him about a Sufi saint because he was grateful I had come. And when he smiled through the few decaying teeth still left in his head, we met in that place again for the briefest of moments, where there’s nowhere to hide, before he turned and walked away. It requires courage to go there, for we are vulnerable, open and honest as nowhere else. And once you leave it, it can be a long road back.

We cannot escape the calamity and complexity of the world breaking and recreating around us daily. It makes the singularity of fundamentalist and extremist ideologies so attractive because it swaps confusion for the clarity of messages that are simple to understand. Compressing complex information into slogans and sound bites, distorted and distilled, is as dangerous as it is deadly. The language of the heart, the mysterious place it resides and its strength cannot be dismissed as it lies in us all. To dismiss it is to dismiss humanity and as bad as things are, we are not there yet.

|

Ingrid Stellmacher, 29/09/2012

|

1 Comment

|

Permalink

|

|

|

Ingrid Stellmacher, 28/09/2012

|

|

|

| |